Recently, I wrote an API that I am very proud of. It’s got 97% test coverage. It aggregates a number of other APIs to accomplish a complicated flow in just two calls. It makes use of two-factor authentication for verification purposes.

I didn’t like how long and branchy my controller code was, though. I started to search around for design patterns or approaches that would enable me to get rid of all the ifs. I found this excellent post on Baeldung that led me to the Rule Engine pattern. From the post: A RuleEngine evaluates the Rules and returns the result based on the input. In the example, each rule’s evaluate method returns true or false. Once any of the rules evaluates to true, processing in the RuleEngine stops. If none of the rules evaluates to true, then an Exception is thrown.

This was very close to what I needed. In my case, the behavior of the RuleEngine needed to be slightly different. Each API call (sometimes to different APIs) returned either a success or failure result. If any API call returns a failure, processing stops. If every API call is succesful, then an overall success result is returned. I called my implementation a StepsEngine where each of a number of Steps is evaluated.

The rest of this post reviews how the code started and where it went. I made a separate project from the production one I described above that still illustrates the approach well. You can find it here on GitHub.

Hitting Every Branch on the Way Down

I’m a huge fan of anime in general and, in particular, of all the Miyazaki films from Studio Ghibli. It turns out a kind soul has made a Studio Ghibli API! This is perfect to demonstrate the StepsEngine approach.

Before we get there, let’s take a look at where the project started. Like any good API, I want to break down my API calls into small chunks in a service. Here’s my GhibliService:

public interface GhibliService {

String BASE_URL = "https://ghibliapi.herokuapp.com";

String PEOPLE_ENDPOINT = BASE_URL + "/people";

String SPECIES_ENDPOINT = BASE_URL + "/species";

String FILMS_ENDPOINT = BASE_URL + "/films";

PeopleResponse listPeople();

PersonResponse findPersonByName(String name);

FilmsResponse listMoviesByUrls(List<String> filmUrls);

SpeciesResponse findSpeciesByUrl(String speciesUrl);

}

For the purposes of demonstration, I want to make a controller endpoint that aggregates a number of calls to the Ghibli API. When a request is made to this endpoint it will:

- search the Ghibli API for a person using a

namethat is passed in - if the person is found, a list of the movies that person appears in is retrieved from the Ghiblie API

- the species that person belongs to is then retrieved from the Ghibli API.

- if all goes well, all of the previous results are returned in a single json response.

NOTE: in the Ghibli API, a Person is any character from a movie, including humans, gods, spirits and animals.

Here’s my first pass at the controller method:

@PostMapping(PERSON_ENDPOINT)

public ServiceHttpResponse findPerson(@RequestBody KeyValueFieldsRequest request, HttpServletResponse response) {

PersonResponse personResponse = ghibliService.findPersonByName(

request.getByName("name")

);

if (personResponse.getStatus() == ServiceHttpResponse.Status.FAILURE) {

return setStatusAndReturn(personResponse, response);

}

Person person = personResponse.getPerson();

FilmsResponse filmsResponse = ghibliService.listMoviesByUrls(

person.getFilmUrls()

);

if (filmsResponse.getStatus() == ServiceHttpResponse.Status.FAILURE) {

return setStatusAndReturn(filmsResponse, response);

}

List<Film> films = filmsResponse.getFilms();

SpeciesResponse speciesResponse = ghibliService.findSpeciesByUrl(

person.getSpeciesUrl()

);

if (speciesResponse.getStatus() == ServiceHttpResponse.Status.FAILURE) {

return setStatusAndReturn(speciesResponse, response);

}

Species species = speciesResponse.getSpecies();

return setStatusAndReturn(new CompositeResponse(

ServiceHttpResponse.Status.SUCCESS, HttpStatus.SC_OK,

"success", person, films, species

), response);

}

It’s not too bad. But, there’s a lot of ifs. In the code I wrote for my real API, there were a lot more of them!

Notice that in between some of the if statements, the result from one service call is passed into the next service call. Also, after each service call, a status check is done. If one of the service calls fails, then the controller will respond with that failure immediately.

The uniform nature of the responses works well. There are specific response types, like PersonResponse, each of which implements the more general base ServiceHttpResponse.

We can easily test this controller for each of the failure possibilities along with the success outcome using Spring Boot’s MockMvc.

Testing the Twists and Turns

In my example code, I am still using Junit 4. While Spring Boot has moved on to Junit 5, I have not yet. Don’t Judge me! (I will get there).

In order to make Junit 4 work with the latest version of Spring Boot, you need the “vintage” engine in your project. Here’s the snippet from my pom.xml:

<dependency>

<groupId>org.junit.vintage</groupId>

<artifactId>junit-vintage-engine</artifactId>

<scope>test</scope>

<exclusions>

<exclusion>

<groupId>org.hamcrest</groupId>

<artifactId>hamcrest-core</artifactId>

</exclusion>

</exclusions>

</dependency>

Gross, I know!

Here’s the real meat of the tests: the set up.

private void setupRequest(

Status personResponseStatus, Status filmsResponseStatus,

Status speciesResponseStatus

) {

PersonResponse personResponse = (personResponseStatus == Status.SUCCESS) ?

new PersonResponse(

Status.SUCCESS, HttpStatus.SC_OK, "success", person

) :

new PersonResponse(Status.FAILURE, HttpStatus.SC_NOT_FOUND, "failure");

FilmsResponse filmsResponse = (filmsResponseStatus == Status.SUCCESS) ?

new FilmsResponse(Status.SUCCESS, HttpStatus.SC_OK, "success", films) :

new FilmsResponse(Status.FAILURE, HttpStatus.SC_BAD_REQUEST, "failure");

SpeciesResponse speciesResponse =

(speciesResponseStatus == Status.SUCCESS) ?

new SpeciesResponse(

Status.SUCCESS, HttpStatus.SC_OK, "success", species

) :

new SpeciesResponse(

Status.FAILURE, HttpStatus.SC_BAD_REQUEST, "failure"

);

when(ghibliService.findPersonByName(NAME)).thenReturn(personResponse);

when(ghibliService.listFilmsByUrls(FILM_URLS)).thenReturn(filmsResponse);

when(ghibliService.findSpeciesByUrl(SPECIES_URL))

.thenReturn(speciesResponse);

}

This method takes three parameters to indicate the expected status of the service calls in the chain of calls that are made in the controller. This makes it easy to have multiple tests with

different conditions for success and failure. The general rule of thumb with this setup is that if the associated service call is expected to succeed, then Status.SUCCESS is passed in. If it’s expected to fail, then Status.FAILURE is passed in. If it’s not expected that the associated service call will be reached (due to a previous failure), null is passed in.

Since all the tests against the controller will be with the same POST request, there’s another helper method to keep the tests small and focused:

private ResultActions doPerform() throws Exception {

return mvc.perform(post(API_URI + API_VERSION_URI + PERSON_ENDPOINT)

.contentType(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

.content(mapper.writeValueAsString(request))

);

}

If you’re not already familiar with Spring’s MockMvc testing features, it provides a compact domain specific language (DSL) for interacting with the controller.

In the above code, I use the MockMvc object’s perform method. I pass perform a call to post with the endpoint already defined in the controller. I’ve also set up the request content as an object, which can be be easily serialized to a string using the mapper built into Spring Boot.

Here’s what one of the tests look like:

@Test

public void personEndpoint_Fail_atFindByPerson() throws Exception {

setupRequest(Status.FAILURE, null, null);

doPerform().andExpect(status().isNotFound());

verify(ghibliService, times(1)).findPersonByName(NAME);

verify(ghibliService, times(0)).listFilmsByUrls(FILM_URLS);

}

Notice that the first parameter in the setupRequest call is a FAILURE status and the other two parameters are null. This lines up with our expectation of the findPersonByName call on the GhibliService failing for this test.

Here’s a snippet from the controller method:

...

PersonResponse personResponse = ghibliService.findPersonByName(request.getByName("name"));

if (personResponse.getStatus() == ServiceHttpResponse.Status.FAILURE) {

return setStatusAndReturn(personResponse, response);

}

...

If the findPersonByName call fails, none of the other service calls will be called as the controller returns at that point. The calls to verify at the end of the test confirm this outcome. We expect that findByPersonName has been called once and that listFilmsByUrls has not been called at all.

Each test exercises the next service call with the previous service calls succeeding. Here’s the second-to-last test:

@Test

public void personEndpoint_Fail_atFindSpecies() throws Exception {

setupRequest(Status.SUCCESS, Status.SUCCESS, Status.FAILURE);

doPerform().andExpect(status().isBadRequest());

verify(ghibliService, times(1)).findPersonByName(NAME);

verify(ghibliService, times(1)).listFilmsByUrls(FILM_URLS);

verify(ghibliService, times(1)).findSpeciesByUrl(SPECIES_URL);

}

Here you can see that the findByPersonName and listFilmsByUrls service calls will succeed while findBySpeciesUrl service call will fail. We verify that each of the service calls have been executed at the end.

The final test is almost exactly the same as the above test with the exception of the setupRequest call:

setupRequest(Status.SUCCESS, Status.SUCCESS, Status.SUCCESS);

In the final test, the expectation is that all the service calls will succeed.

The point of all these tests is that after we refactor the controller code to take advantage of the StepsEngine, the tests should all still pass.

Step it up to the Next Level

The goal here is to get rid of all the branching in the controller, while still keeping the code readable and having all the tests pass.

Spoiler Alert! Here’s the final form of the controller method:

@PostMapping(PERSON_BY_ENGINE_ENDPOINT)

public ServiceHttpResponse findPersonEngineStyle(

@RequestBody KeyValueFieldsRequest request, HttpServletResponse response

) {

StepsEngine stepsEngine = setupEngine();

ServiceHttpResponse serviceHttpResponse = stepsEngine.process(request);

return setStatusAndReturn(serviceHttpResponse, response);

}

Three lines! Not too shabby! And, the setupEngine method is pretty lean too:

private StepsEngine setupEngine() {

StepsEngine stepsEngine = new StepsEngine();

stepsEngine.addStep(new PersonResponseStep(ghibliService));

stepsEngine.addStep(new FilmsResponseStep(ghibliService));

stepsEngine.addStep(new SpeciesResponseStep(ghibliService));

stepsEngine.addStep(new CompositeResponseStep());

return stepsEngine;

}

Examining the setupEngine method, you can see the order of the steps:

PersonResponseStepFilmsResponseStepSpeciesResponseStepCompositeResponseStep

If any of these steps fails, we expect that our controller will return an appropriate failure response. If all the steps succeed, we expcet that our controller will return the CompositeResponse.

How is all this accomplished with our 3-line controller method? It seems like magic! It’s really a combination of the Java 8 streams api and Java generics that allows the system to work. Let’s look deeper.

At the heart of the system is the Step interface:

public interface Step {

Status evaluate(KeyValueFieldsRequest request);

ServiceHttpResponse getResponse();

}

Every step, when evaluated, takes a uniform request object as a parameter and returns a Status. Status is an enum with two values: SUCCESS and FAILURE.

There’s also a getResponse method that returns a ServiceHttpResponse object. There are a number of implementations of ServiceHttpResponse that we’ll review below.

Here’s the first step implementation:

public class PersonResponseStep implements Step {

private final GhibliService ghibliService;

private PersonResponse personResponse;

public PersonResponseStep(GhibliService ghibliService) {

this.ghibliService = ghibliService;

}

@Override

public Status evaluate(KeyValueFieldsRequest request) {

personResponse = ghibliService.findPersonByName(

request.getByName("name")

);

return personResponse.getStatus();

}

@Override

public ServiceHttpResponse getResponse() {

return personResponse;

}

}

The step requires the GhibliService, so it’s passed into the constructor. This pattern works well when you have a number of services that interact with different APIs.

Let’s take a look at the StepsEngine itself to see just how the engine works.

public class StepsEngine {

private final List<Step> steps = new ArrayList<>();

public void addStep(Step step) {

steps.add(step);

}

public ServiceHttpResponse process(KeyValueFieldsRequest request) {

Step step = steps.stream()

.filter(s -> s.evaluate(request) == Status.FAILURE)

.findFirst()

// if nothing fails, last step must be success

.orElse(steps.get(steps.size()-1));

return step.getResponse();

}

}

Here’s where the magic of the streams interface (introduced in Java 8) comes into play.

There’s a List of steps that gets filled out through the addStep method.

The process method takes in the request object that all the steps must know how to handle.

The line with .filter calls the evaluate method of each of the steps and returns that step if the Status is FAILURE.

The call to findFirst() ensures that the stream is interrupted if a FAILURE occurs. The step that failed is assigned to the step variable.

Finally, the orElse is hit when all steps have run successfully. In that case, the last step is assigned to the step variable. It is therefore important that you define a step that represents your overall success state and that it be the last step in your list.

After the stream is done - whether the result is success of failure - the ServiceHttpResponse from the assigned step is returned.

This is all pretty straightforward so far, but there’s a problem that you run into almost right away. That problem is state.

Look at this snippet from the original controller method:

PersonResponse personResponse = ghibliService.findPersonByName(

request.getByName("name")

);

...

Person person = personResponse.getPerson();

FilmsResponse filmsResponse = ghibliService.listFilmsByUrls(

person.getFilmUrls()

);

Here, we’re passing the result of one service call into the method of the next service call.

In order for our StepsEngine to function properly, we’re going to need to save state.

Here’s the updated Step interface:

public interface Step {

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

default <T> T fetchState(String key) {

return (T) getStateContainer().get(key);

}

default void saveState(String key, Object value) {

getStateContainer().put(key, value);

}

Map<String, Object> getStateContainer();

void setStateContainer(Map<String, Object> stateContainer);

Status evaluate(KeyValueFieldsRequest request);

ServiceHttpResponse getResponse();

...

}

a Map<String, Object> is a handy and cheap way to save state along the way. It accomodates saving various types of objects in a flow that can have many steps.

However, casting can get annoying, so I use some generics magic to alleviate that. That’s what the fetchState method is for.

Since all the steps must now implement getStateContainer and setStateContainer, it’s useful to introduce an abstract class that implements those two methods. The various step classes can then just extend that abstract class.

public abstract class BasicStep implements Step {

private Map<String, Object> stateContainer;

@Override

public void setStateContainer(Map<String, Object> stateContainer) {

this.stateContainer = stateContainer;

}

@Override

public Map<String, Object> getStateContainer() {

return this.stateContainer;

}

}

Now, Let’s take a look at the refactored PersonResponseStep:

public class PersonResponseStep extends BasicStep {

public static final String PERSON_KEY = "person";

...

@Override

public Status evaluate(KeyValueFieldsRequest request) {

personResponse = ghibliService.findPersonByName(

request.getByName("name")

);

saveState(PERSON_KEY, personResponse.getPerson());

return personResponse.getStatus();

}

...

}

Each step is responsible for defining the key that will be used in the state container. In this case, the saveState method is called with the PERSON_KEY and the Person object from the PersonResponse.

Take a look at the next step in the chain, FilmsResponseStep:

public class FilmsResponseStep extends BasicStep {

public static final String FILMS_KEY = "films";

...

@Override

public Status evaluate(KeyValueFieldsRequest request) {

Person person = fetchState(PERSON_KEY);

filmsResponse = ghibliService.listFilmsByUrls(person.getFilmUrls());

saveState(FILMS_KEY, filmsResponse.getFilms());

return filmsResponse.getStatus();

}

...

}

In its evaluate method, it uses fetchState to get the Person from the state container. Because of the generics used in the definition of the method in the Step interface, a cast

is not required here.

Now the service method can be called with the Person object retrieved from the state container. This step adds to the state container with its defined key FILMS_KEY after the service call.

The StepsEngine along with the generified stateContainer makes the whole system hang together.

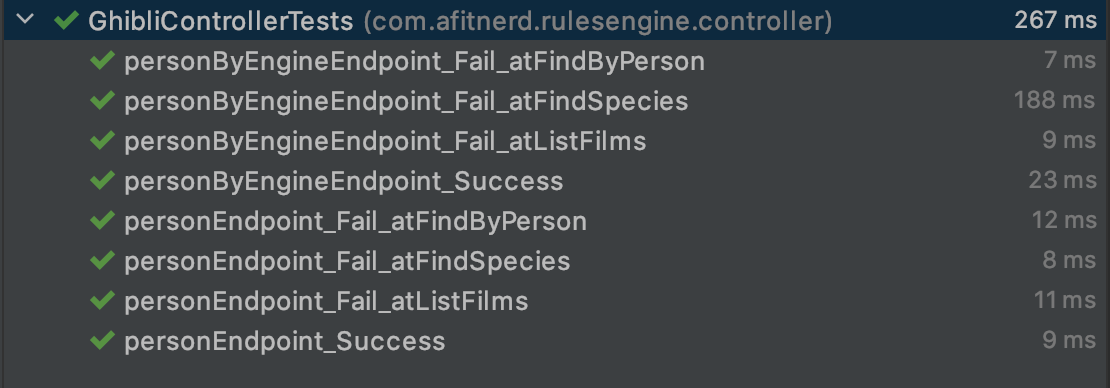

Revisiting the Tests with the Engine

Now that we’ve refactored the pieces of the original controller method to use the StepsEngine, all our tests should still pass. As a reminder, here’s what the controller method now looks like:

@PostMapping(PERSON_BY_ENGINE_ENDPOINT)

public ServiceHttpResponse findPersonEngineStyle(

@RequestBody KeyValueFieldsRequest request, HttpServletResponse response

) {

StepsEngine stepsEngine = setupEngine();

ServiceHttpResponse serviceHttpResponse = stepsEngine.process(request);

return setStatusAndReturn(serviceHttpResponse, response);

}

If you remember from before, I showed you the doPerform method that sets up the MockMvc request to call the controller endpoint. In order to support both the steps engine and branching approaches in the controller, I have two endpoints: PERSON_ENDPOINT and PERSON_BY_ENGINE_ENDPOINT. In the controller test, I have two setup methods each of which calls a base method to get everything set up with one endpoint or the other:

private ResultActions doPerformBase(String endpoint) throws Exception {

return mvc.perform(post(endpoint)

.contentType(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

.content(mapper.writeValueAsString(request))

);

}

private ResultActions doPerform() throws Exception {

return doPerformBase(API_URI + API_VERSION_URI + PERSON_ENDPOINT);

}

private ResultActions doPerformByEngine() throws Exception {

return doPerformBase(API_URI + API_VERSION_URI + PERSON_BY_ENGINE_ENDPOINT);

}

Now I can run tests against both endpoints and they should all pass. And, as you can see below, they all do!

Get Your Engines running

Hopefully you’ve found this post useful in how to reduce branching in your controllers. There are a number of pros and cons to the Rules Engine approach taken here:

Pros:

- very compact controller code

- encapsulation of steps in their own classes

- easy to test

- works great in situations with multiple external apis with lots of steps

Cons:

- more classes (one per step)

- need to maintain state

- might require more hunting around for code to understand the flow

You can find my demo project here on Github.

The original post that this work is based on is on Baeldung.

You can find me on twitter: @afitnerd